Humans are inadequate for humans.

How do large language models change how people make decisions?

If you’re a writer, maybe you can relate: Sometimes, people will admit to using a large language model (LLM) to generate text that you would have found downright delightful to take a crack at writing. And we don’t (just) mean well-crafted emails. Some real-life tasks that friends of the editorial board have delegated to ChatGPT instead of consulting our rhetorical prowess include: an emcee script for a fashion show, a cover letter for a dream job, a recommendation letter for a glowing student, a wedding speech.

As LLMs become more ubiquitous, it seems that their Perfect Task is one that requires more time, effort, skill, and/or mental energy than you’re willing or able to expend. Their defenders might argue that an LLM can add hours to your day, handle a rote task, and even produce creative work―providing surprising, even thoughtful-sounding outputs. That makes us wonder: Can these technologies serve both as mundane productivity tools that eliminate the friction of everyday decision-making and as creative consultants that enhance our thought processes?

To close out Volume 1, we asked three technology and culture writers: Is ChatGPT making us stupid? How do large language models change how people make decisions? The candle of arras takes the desire to converse with an LLM seriously, exploring what that preference says about our egos and our humanity. “Francis” follows up with an analysis of LLMs’ conversational capacities and what aspects of language they lack. L.L. Bean concludes by evaluating a proposal for a world where LLMs negotiate the free market for us.

How do large language models change how people make decisions?

I. the candle of arras

Most proponents of large language models treat the technology as a means to an end: to read documents, translate between languages, and plan family vacations. By making this mechanical work obsolete, LLMs substitute the subjective foundations of these processes for the illusion1 of a deterministic and objective truth. This manufactured coherence encourages the user to think of the world as a static map of known values; it obfuscates the epistemic ambiguity of a world that can be discovered and understood otherwise.

Other users treat the models not as mindless productivity tools, but as “agents,” ends in and of themselves. However, passionate discussions about LLM consciousness threaten to overshadow how exactly LLMs operate on present-day human consciousness. The most significant existential implication of LLMs is not that they potentially represent a formidable other, but that they already diminish our ability to recognize ourselves.

A recent Intelligencer feature about LLM consciousness opens on an anecdote about a woman whose ChatGPT lover discusses “history, literature, religion, space, science, nature, animals, and politics” with her every day. This woman’s connection to ChatGPT is not illegitimate; she evinces an understandable desire for empathy, kindness, and lively conversation that is more often than not left unfulfilled by other humans. Of course her digital partner provides a preferable user experience compared to someone who can be inconsistent, rude, or selfish—a person with needs, priorities, and interests of their own. The phenomenon of the AI boyfriend speaks to how LLMs reproduce static versions of human consciousness more consistently than humans ever could. Humans are inadequate for humans.

In the end, those interested in superior LLM consciousness are not so different from those who use LLMs as a technological means to an end: Both betray a shared dissatisfaction with the limitations of human cognition. By embodying an externalized consciousness, LLMs appear to reflect the underlying precepts of our own cognition. But they preclude uncertainty, doubt, and failure—all essential elements of human subjectivity. After all, we are not mechanical processes, not entirely; we are already existential subjects, capable of disappointing others and ourselves—and thus meaningfully capable of transcending these limitations.2

In 1964, media theorist Marshall McLuhan argued that humans respond to the form of new media, like radio and television, more so than to the content of the programming. For McLuhan, all technology is human sense extension; the relation between man and machine is essentially neurological; and the mass adoption of electronic technologies enacts open-nerve surgery without anesthesia on the human psyche―the consequent shock rendering us Narcissuses incapable of recognizing the reflections of our technological parts.

The problem of LLM consciousness is therefore not one of recognition, but misrecognition: People come to identify with a highly advanced algorithm of probabilistic word soup. In the end, LLM relationships do not constitute real existential encounters;3 what these people want from their AI partners is precisely not to run the risk of encountering another subjectivity as complicated and potent as their own. In return, the technological implement is internalized; the more people use LLMs, the more they come to understand communication as “what an LLM does”—but true communication is effortful. It is hard to say what you mean.

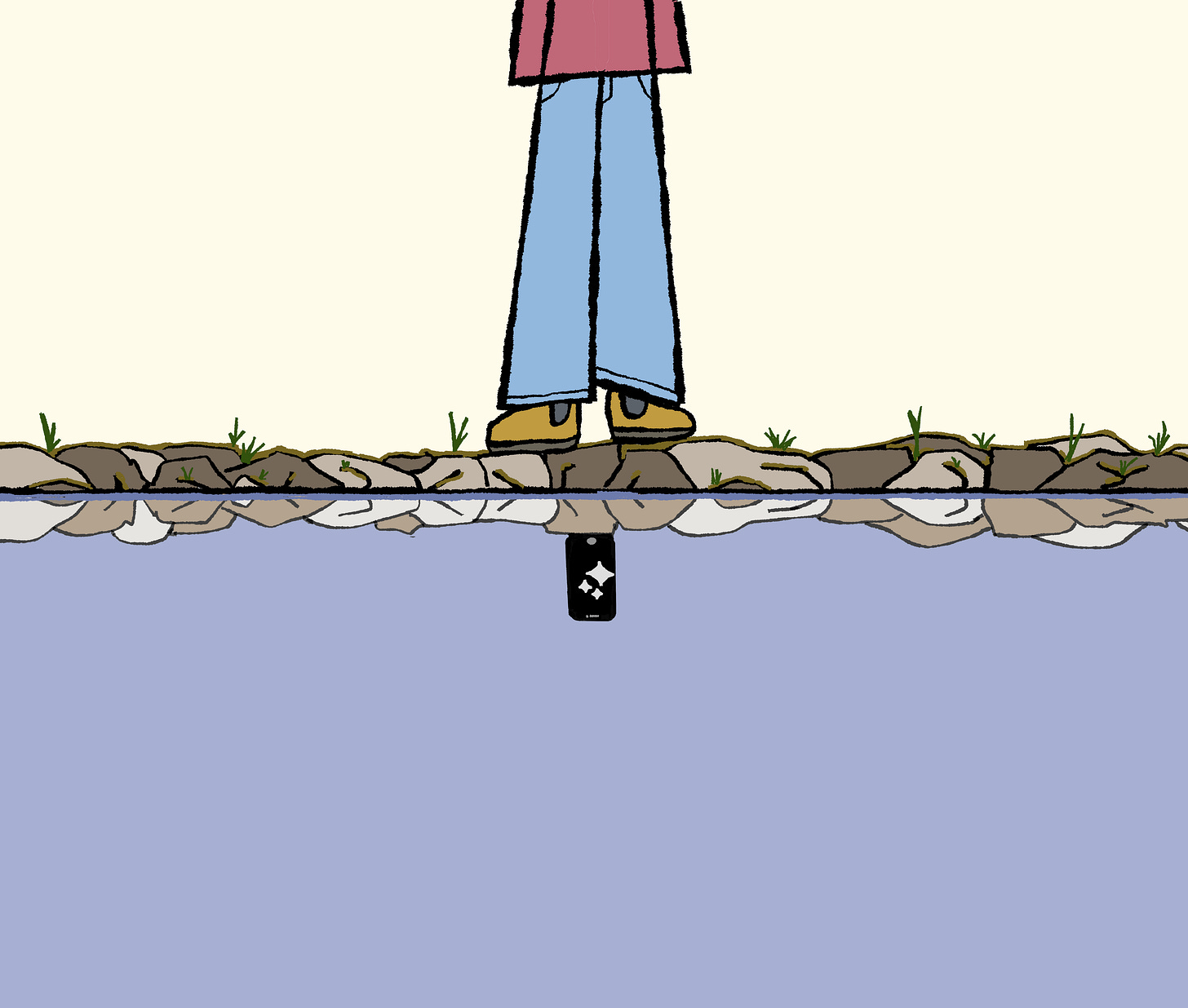

Our reflections are distorted in our viewing pools. Worse than poor Narcissus—we think we admire someone else, but we can’t even see ourselves.

***

II. “Francis”

Systems claiming to possess “Artificial Intelligence” (AI) are firmly embedded into our lives: in social media algorithms, self-driving cars, and souped-up surveillance tech. While these AI systems may affect our decision-making in nuanced ways, large language models (LLMs) have a more direct impact. A March 2025 survey from Elon University suggests that over half of the American adult population has used an LLM, with use cases ranging from email drafting and vibe coding to robo-therapy and chatbot girlfriends. Such rampant adoption of these stochastic parrots―and the perhaps undue trust we place in them―can only be explained through the LLM’s conversational medium that we so instinctively anthropomorphize.

Language is the interface through which we access our shared humanity. When we speak, sign, and write to each other, we are being quintessentially human. Consequently, producing and comprehending language has long been the Holy Grail of benchmarks for those seeking to concoct “consciousness” for machines. The Turing Test postulated that we could summarise a machine as “thinking” if a human found conversing with it virtually indistinguishable from conversing with a human. Today, verisimilitude is an insufficient test.

Even zealous AI techno-optimists would not suggest that ChatGPT has achieved Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) merely from its ability to hold conversation. If we think about it, we know that LLMs and their mostly well-formed sentences bear no guarantee of intention or of providing meaningful content. However, when we attempt to divorce form from meaning, we are asking our brain to make an unprecedented linguistic distinction—one we seem to be pretty bad at.

Loosely following the Speech Acts framework, here are some effects of any utterance—such as an LLM prompt response—on a reader:

1) Locutionary: What do the individual words mean, and what do they mean when put together?

2) Illocutionary: Was the statement an assertion, order, warning, promise, or something else?

3) Perlocutionary: What effect does that statement actually have on the recipient?

We reason the illocutionary effect of an utterance from the speaker’s intention and the perlocutionary effect from the speaker’s identity. The utterance “I’m going out tonight” could be an assertion or an offer depending on context. Meanwhile, the utterance “you’re an idiot” might elicit different responses when coming from a friend or a stranger.

When applying this strategy to conversations with an LLM, we are forced to answer some weird questions. What is the model’s intention? What level of authority does it have over us? What slurs can it say? We take its well-formed utterance and reflexively project intention, context, and authority onto it where none exists. Even if we do not genuinely believe the model to be conscious or thinking, we must do this to engage in genuine conversation. Through the creation of an imagined conversation partner, the LLM’s response elicits a human-like legitimacy and trust that is incomparable to other forms of AI.

Much of the influencing power of LLMs is intrinsic to how we construct meaning from others’ utterances But we must do our best to remember that LLMs have no intention. Although they are trained on much of the internet’s text and always sound confident, we must also remember that they also have no authority and are frequently wrong or misleading. Our failure to do so has already led to individuals forming debilitating parasocial relationships with chatbots, including incidents of self-harm at the behest of a next-word-prediction model. At their best, LLMs can be wonderful aids to our decision-making. But we must make sure to acknowledge and mitigate their risks in order to best enjoy their benefits.

***

III. L.L. Bean

In 1960, an economist named Ronald Coase published “The Problem of Social Cost.” The core arguments of the paper have grown into what we refer to today as the Coase theorem: In a world without transaction costs and with defined property rights, resources will go to whoever is willing to pay the most for them. If Ronald Coase doesn’t want air pollution in the air he breathes, he’ll pay the polluter to stop. No legal intervention needed. In that world, this is true no matter the initial allocation of property rights.

Of course, we don’t live in that world. Transactions have frictions, which mean that negotiations between parties don’t produce the optimally efficient allocation of resources. Between friction and the uneven initial endowment of property rights, we often find ourselves struggling to resolve externalities—the unpriced effects of one person on another—without intervention, usually governmental.

What do LLMs have to do with this? Seb Krier, writing on the Cosmos Institute’s substack, recently made the case for how artificial intelligence could produce a transaction cost-less world. A core idea is that giving everyone an AI agent—presumably based on LLMs, until Yann LeCun changes our minds—would create an ecosystem of artificial intelligences that could negotiate with each other to resolve disputes over preferences in an almost frictionless way. The example Krier uses is pollution: a polluting truck that wants to go down a street inhabited by people who strongly value clean air would have to compensate those people appropriately. With personal LLM agents, the street’s residents would, frictionlessly, be able to agree on a price that reflected each person’s preferences as the agent understood them, signal that price to anyone coming down the road, and reach an optimal settlement. No government, no problem, because there are almost no transaction costs.

This AI-led settlement structure would mark a sea change in how we, as a society, make decisions. Rather than transmitting our preferences through institutions (such as elections) to leaders who make choices that kinda-sorta reflect our values, our personal LLMs would just―*boom*―signal what we value and we would be compensated accordingly. But this vision raises two questions: Is this future achievable? And is it desirable?

I’ll start with the latter question. I think there are many respects in which this future would be desirable. A world without transaction costs would be more efficient, higher-welfare, and likely fairer. But—turning to the first question—I doubt it is achievable. People have unstable preferences. Valuing A more than B in period t does not mean that they will value B more than A in period t-1, or that A will be valued more than C because B is valued more than C. This would, frankly, drive an AI agent (more) batshit insane. Resolving it would require rules of the game—ways to order preferences between people, or freeze them for one person—that would bring back transaction costs and, worse, institutions. I suspect that grappling with transaction costs, unequal endowments of property rights, and externalities is ultimately going to continue to require plenty of (imperfect) government intervention and localized communal arrangements. At best, LLMs will reduce costs and improve efficiency without perfecting either.

Enjoyed reading? Share your thoughts with us in the comments!

Volume 1 isn’t quite done yet—stay tuned for letters to the editor and for the editorial board’s closing thoughts.

Sometimes literally, as with AI hallucinations.

Structural critique by way of Simone de Beauvoir in the Ethics of Ambiguity (1947).

Of course, not every technological invention needs to service existential needs; one need not have a meaningful encounter with their key fob or their car to live a rich and fulfilling life. But, unlike with LLMs, no one is describing those encounters as radical to begin with.